Somber Anniversaries

- By Christopher Nord

- •

- 01 May, 2018

It's been 32 years since Chernobyl. What have we learned?

The other day, I was handed a check from a customer, and realized that it was the 26th of April. I then played the “Do you know what anniversary it is?” game—for which regular folks usually have no clue.

It was a long time ago, 32 years, when a radioactive cloud spread into the upper atmosphere from Ukraine, eventually causing alarm in milk-testing stations on the West Coast of the US. Much of the reindeer herd of Lapland had to be euthanized due to radiation exposure; and the entire 18-mile “exclusion zone” around the Chernobyl reactor was transformed to a kind of ghost town, including the city within the zone that housed and served Chernobyl’s workers and their families.

All of the men who responded to the immediate need to build a “sarcophagus” over the exploded reactor later died of acute radiation sickness. And lo’ these many years later, they still have an on-going nuclear reaction taking place within the mass of molten fuel—something from which the entire web of life must be protected, way beyond any foreseeable future, because of the extremely long “toxic lives” of some of the radionuclides being generated.

All of this is one potential outcome from generating electricity via atomic fission—a process that Dr. Amory Lovins, founder of the Rocky Mountain Institute, has likened to “cutting butter with a chainsaw.” Predictably, corporations and regulatory agencies here in the States quelled concern over the 1986 accident by asserting that the kind of event that blew up in Ukraine literally could not happen here—because our reactors are structured and controlled completely differently than Chernobyl.

I was skiing with my partner Lisa at Wildcat Mountain on March 10, 2011; and at the end of the day drove back to the condominium where friends had hosted us, to say goodbye before driving home. My buddy Will was watching a movie, “The Day After Tomorrow;” and I stood transfixed by the images of streets being inundated by the ocean. The next morning when I got downstairs and turned on the news, I felt momentarily confused by what appeared on the T.V., as images of the tsunami hitting Japan filled the screen.

Of course, we know now that while the damage wrought directly by the tsunami crashing inshore was devastating, the greater impact came a few days later, when a series of steam explosions literally blew the tops off four General Electric Mk1 reactors at Fukushima, eventually leading to the “meltdown” of their reactor fuel (ironically due to the lack of available electricity to pump cooling water).

Seven years later, they still have uncontrolled fission occurring, and have had to devise structures to seal in the toxins. Not the same genesis of events as Chernobyl—but in some crucial ways a very similar outcome.

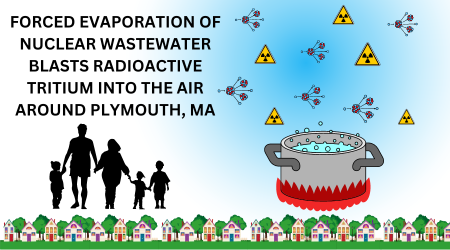

It’s worth noting that the Pilgrim atomic plant on the South Shore of Massachusetts is the same type of reactor as the destroyed plants of Fukushima—a type which General Electric’s own engineers tried to warn them about. We can only hope Pilgrim is shut down in 2019 without any more disasters, and all the radioactive inventory can be removed from the immediate danger of coastal flooding. But whose back yard shall we send it to?

It is ironic that most Americans actually know more about the accidents at Chernobyl and Fukushima than they do about our very own, homegrown meltdown at Three Mile Island (TMI). It makes spring a busy season for inauspicious anniversaries (March 28, 1979). It turns out, the night of the accident initiation, I was handing out flyers about the health effects of radiation at a showing of the movie “China Syndrome;” the title is another term for “meltdown.”

The reasons for us to remember the TMI disaster are many; but one important fact for those of us near Seabrook Station is that unlike Chernobyl or Fukushima, TMI’s two reactors are the same basic type of design as the one in our New Hampshire saltmarsh: Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR).

Another important fact about TMI is that the requirement for evacuation plans at US commercial reactors was instituted only after the 1979 accident—and years after Seabrook had been sited, and construction was under way. Subsequently, more than half the municipalities within this 10-mile radius declared the un-workability of the evacuation plans in the lead-up to licensing in 1990.

In the evolution of New Hampshire and Massachusetts energy strategies, one has to wonder what real consideration is given to the actual workability of “Emergency Response Plans” for the areas around their atomic plants? At least in our area, the population has doubled since the Federal Emergency Management Agency Region I Chief Ed Thomas rejected the plans for our reactor community in the late 1980s.

Today, there are approximately 160,000 year-round residents within the 10-mile Emergency Planning Zone of Seabrook. Many of who are women and children with rapidly dividing cells—and therefore as much as twenty times the vulnerability to the effects of radiation as I, an adult male, face. Are we certain people in nuclear reactor communities are being properly protected? As I consider these somber anniversaries, I truly wish that they were.

Follow us