Nuclear waste and environmental justice

- By Sarah Doenmez, C-10 Board Member

- •

- 07 Oct, 2021

The shared legacy of atomic power, and the need for consent-based siting

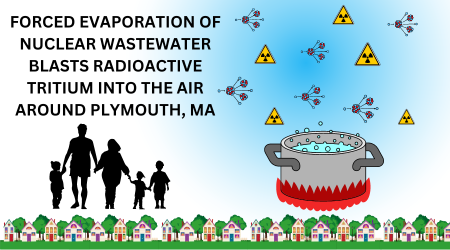

As an organization concerned with the health and safety of people and the natural environment, C-10 understands that the wellbeing of our own community and the energy generated to support our regional economy is inextricably linked to the people and places affected by the entire life cycle of nuclear power. This cycle includes mining and processing, transport, and ultimately the storage of waste that will be deadly toxic for a million years, or more.

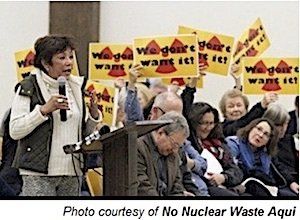

C-10 is deeply troubled that waste from energy generated to power the New England economy could end up poisoning under-represented indigenous and minority populations far away. With decades of waste piling up, communities in other regions of the country are being asked to shoulder an unfair burden.

An unending and toxic legacy

The legacy of nuclear waste is terrifying to contemplate. All generation of nuclear power results in toxic waste products, some of which have short half-lives and quickly decay into materials such as lead. Other compounds will be hazardous to living creatures for millions of years. Uranium 239 has a half life of 240,000 years; Uranium 238’s half life is 4.5 billion years. Neptunium - 237’s halflife is 2 million years, and Iodine-129’s is 17 million years.

These elements can be present in both high-level and low-level radioactive waste, and are created both by nuclear weapons production and by nuclear energy reactors. The US Government Accounting Office states that our nation has generated 80,000 metric tons of high-level radioactive waste from nuclear energy reactors, and 90 millions gallons of high level radioactive waste from nuclear weapons. That’s a lot of waste—and the figure does not include low-level waste.

Nuclear waste will continue to emit radioactivity harmful to humans and the environment for longer than we can contemplate. While we can hope that facilities for storing nuclear waste will prevent most of us from direct exposure to these poisons, it is difficult to imagine human-built structures that will never crack or leak radioactivity into the water or the environment; some of the waste storage casks are designed to last for 100 years; the numbers just don’t add up.

According to the NRC’s Backgrounder on Radioactive Waste, “High-level wastes are hazardous because they produce fatal radiation doses during short periods of direct exposure. For example, 10 years after removal from a reactor, the surface dose rate for a typical spent fuel assembly exceeds 10,000 rem/hour—far greater than the fatal whole-body dose for humans of about 500 rem received all at once. If isotopes from these high-level wastes get into groundwater or rivers, they may enter food chains. The dose produced through this indirect exposure would be much smaller than a direct-exposure dose, but a much larger population could be exposed.”

This description of the dangers of spent fuel rods from nuclear reactors is only one source of nuclear waste; there are many others.

The federal government’s recent decision to build a repository for high-level waste on Western Shoshone land is in violation of treaty protections and was made without consent from the people, or the state.

This plan also runs counter to a 1994 executive order by President Bill Clinton. President Clinton issued the order requiring federal agencies to consider environmental justice issues when issuing permits for new polluting facilities. Although, as an independent agency, the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission was exempt from the order, then-Chairman Ivan Selin committed the NRC to implementing it.

The state of New Mexico has sued the NRC over its waste disposal plan. In his complaint, New Mexico’s Attorney General Hector Balderas outlined the risks his state's citizens would face if the facilities are built. “I am taking legal action because I want to mitigate dangers to our environment and to other energy sectors,” he said in a statement. “It is fundamentally unfair for our residents to bear the risks of open ended uncertainty.” Read more in this C-10 blog from May 2020.

“We take it as our mission to try to ensure the safety, health, and security of our nearby residents,” said Christopher Nord, founding board member of C-10. “We must monitor the fuel chain, because Seabrook Station’s effects live on, far beyond our ingestion pathway.”

C-10 believes it is our responsibility to advocate for the safest ways to manage nuclear waste, as outlined in our May 2021 Policy Paper on Environmental Justice.

Decades of power, no permanent solution

The US Department of Energy (DOE) is the federal agency in charge of developing plans to dispose of commercially generated nuclear waste, and for commissioning the facilities to enact those plans. Because of the many complexities of this task, and its expense, the DOE has not yet settled on a workable strategy for safely storing radioactive waste even as quantities of the materials continue to be produced. Spent fuel rods from nuclear reactors are mostly stored in dry casks at the nuclear power plants where the waste was created.

But this is not an option for all forms of high level waste. Yucca Mountain, once hoped by some to be the solution to the nation’s nuclear waste problem despite geological and environmental justice concerns, suffered an explosion in 2014 and is no longer considered a viable option.

Most experts agree that high-level waste must be stored underground in carefully chosen locations with carefully constructed chambers that can be carefully monitored. But where should these be located?

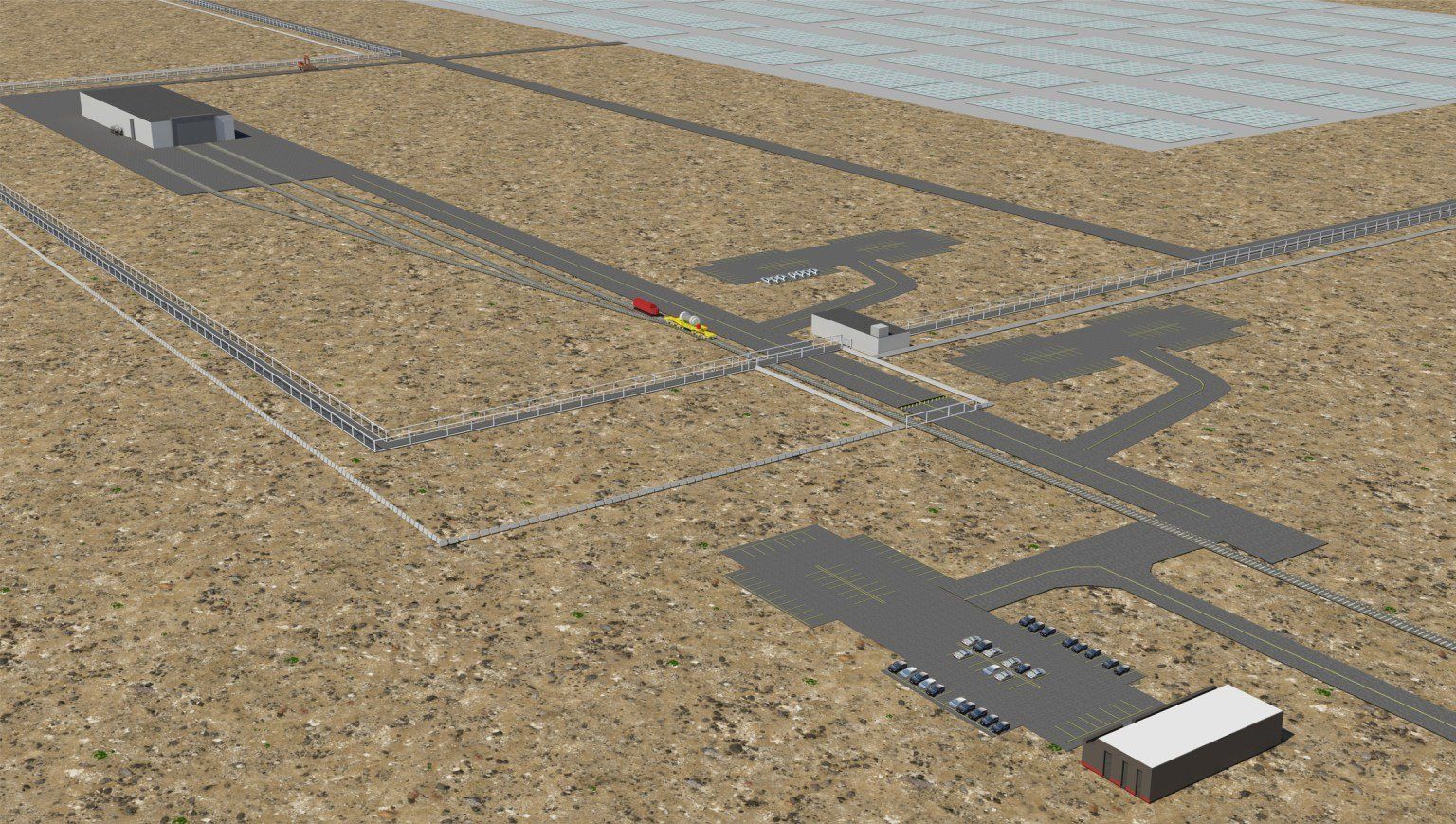

Under pressure from the nuclear industry to provide solutions, the DOE is now allowing private companies to take on this problem. Holtec International has proposed so-called “interim” storage sites in New Mexico.

Interim Storage Partners (ISP) has proposed a site in western Texas. ISP proposes an initial 40-year license to consolidate and store an eventual total of 40,000 metric ton of used nuclear fuel, developed over eight flexible phases.

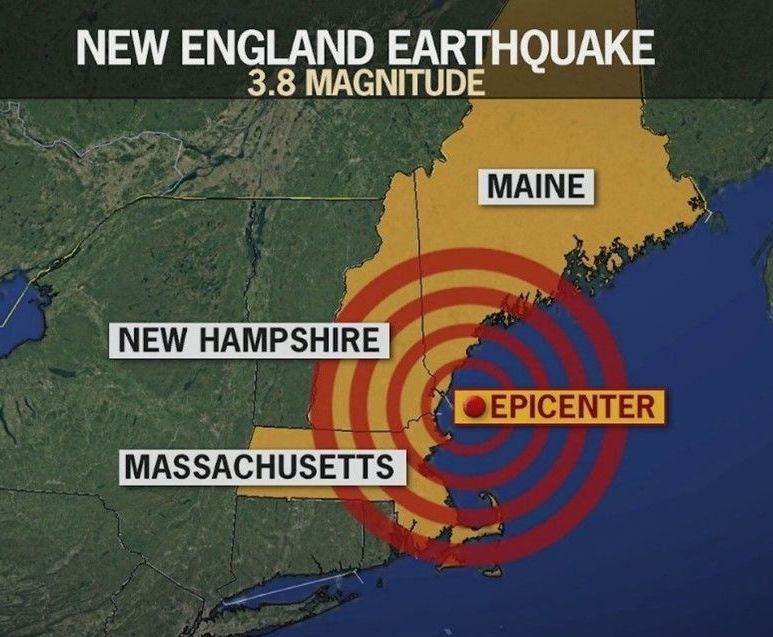

The NRC has been reviewing these proposals, and has already greenlighted the west Texas proposal. Both of these proposals would involve moving the nation’s high-level waste by shipping it by rail and on trucks to sites in western Texas and New Mexico, to Shoshone lands.

The dangers created by shipping high-level radioactive materials across the nation on our roadways and railroads is clear. These “solutions” place our nation’s waste on lands of poorer and more vulnerable citizens. Indigenous communities in the Southwest have suffered repeated exposures to radioactivity from uranium mining and as downwinders of the nation’s nuclear testing grounds.

To put high level waste generated at Seabrook Station to meet New England’s energy needs onto Native land in the Southwest would put these communities at further risk of exposure and long-term health effects. Our nation has a well-established pattern of making our more vulnerable and less powerful citizens face unacceptable environmental pollution and suffer its effects.

The need for consent-based siting

C-10 believes that nuclear waste should stay in the states in which it is created and should be stored in suitable locations with consent of the communities likely to be affected. Proposed host communities must clearly understand the risks associated with exposure to radioactivity, the storage facilities, and their rights.

The DOE has committed to using this process, and started exploring this method, by gathering input following the recommendation of the Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future in 2012. The DOE has stated, “The Strategy endorses a phased, adaptive, and consent-based approach to siting and implementing a comprehensive management and disposal system.” It gathered a first round of public input, which raised a host of issues.

According to A Better Way To Store Nuclear Waste: Ask for Consent by scientists Seth Tuler and Thomas Webler writing in The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, consent-based siting is used in several other countries, and is endorsed by leading nuclear safety organizations.

The government knows that consent-based siting is the right way to proceed. C-10 calls on the Department of Energy and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to follow these commitments and not to cut corners by endorsing solutions that perpetuate our nation’s history of environmental injustice.

Consent-Based Siting requires those of us who use nuclear energy to take responsibility for its by-products. This also forces all of us to face the dangers we allow as the price of our energy consumption. It is the right thing to do.

What actions could the NRC take to enhance consideration of environmental justice in the NRC's programs, policies and activities and agency decision-making, considering the agency's mission and statutory authority?

So, what do YOU think about environmental justice and nuclear power issues? The NRC wants to hear from you!

See this link on NRC's website to learn more and see a list of questions to get you thinking.

Comments will be accepted through October 29, 2021. You may submit comments through the following:

Voicemail at 301-415-3875 or 800-882-4672

Email at NRC-EJReview@nrc.gov

The Federal rulemaking site, www.regulations.gov, using Docket ID NRC-2021-0137

Mail comments to: Office of Administration, Mail Stop: TWFN-7-A60M, U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Washington, DC 20555-0001, ATTN: Program Management Announcements and Editing Staff.

Read C-10's comments, submitted to NRC on October 20, 2021.

Follow us